|

||||

|

BUFFALO BY BOAT *

A PLACE OF MAGNIFICENT SOLITUDE *

DROUGHT AND "PROBLEM" ELEPHANTS *

WHEN NIGHT FALLS IN AFRICA *

THE EYES IN THE BUSH THAT WATCHES YOU …WHILE YOU ARE HUNTING *

KING OF THE MOUNTAINS *

A NAMIBIAN ALTERNATIVE TO TROPHY HUNTING * NEVER SHY OF HARD WORK - PROFILE OF ANTON ESTERHUIZEN * CHOOSING HEAVEN BUFFALO BY BOAT

By Adam Heggenstaller, Editor in Chief, Shooting Illustrated

In the floodplains of the Caprivi Strip, hunting dangerous game sometimes means taking to the water. When the pounding rains of the wet season end in March, the part of Namibia's Caprivi Strip stretching southeast from the village of Katima Mulilo seems to be more water than land. The low-lying region becomes pinched by the swollen Zambezi and Chobe rivers that spill across their wide floodplains, turning previously dusty flats into sodden expanses covered with grass and game. Enough water remains a month and a half later to cover my boots and most of my lower legs as I follow PH Anton Esterhuizen across the sopping terrain behind Kasika, a small cluster of mud-and-thatch huts on the edge of the concession where we've come to hunt buffalo. Its 6:30 in the morning, the sun has not yet risen above the high hill across the Chobe in Botswana, and at least for now the goose bumps on my arms are the result of bare skin being exposed to cool air and water. Anton wears sandals and, grinning, looks like he wouldn't mind a swim. He knows in a couple hours we'll both be sweating. Logistics are a big part of any safari, and on this trip the abundant water dictated our approach. By road, Kasika was about 150 miles east of our well-appointed base camp. With part of the route being submerged, the only practical way to the concession came mainly by river. Yesterday started with a short boat ride out of camp, crossing the swamp-like floodplain of yet another river named the Kwando, squeezing through a narrow channel that wound among thick stands of 12-foot-tall reeds penetrable only by beasts of substantial bulk like elephant and hippo. After driving to Katima, we spent most of the day running a J-shaped course down the Zambezi and then up the adjoining Chobe in a 16-foot pontoon boat equipped with twin 50-horsepower outboards, arriving at Kasika late in the afternoon. This morning on the floodplain, the boat is much smaller, exclusively man-powered and not nearly as stable. When a quarter-mile of wading brings us to deeper water, two villagers are waiting in a dugout mokoro. Sitting low in the water and not much wider than a man, the typical 8- to 10-foot Caprivi mokoro is a boat only in the sense that it has sides and floats most of time. As I carefully step into one of the slim, solid-wood crafts and feel it start to lean under my weight, I remember the sign back at the landing warning boaters, tourists and other two-legged, tender pieces of meat about the ever-present crocodiles. I kneel in the bottom of the mokoro, which is already covered in a couple inches of water, and hang on to the hand-carved gunwale like it's going to help. The lean natives, obviously much more trusting of both their boat and their balance, stand erect at either end of the mokoro and use long-handled oars to half push, half paddle us across the plain. Our destination is a large island of slightly higher, tree-covered ground where game scouts spotted a herd of buffalo the previous afternoon. Anton and I reach it without incident, not much wetter than when we started, and watch the boatmen skillfully glide their version of a canoe back across the flooded land to retrieve the rest of our party. It takes several trips; there are quite a few of us along on this hunt. As we gather in a rough semicircle around Anton, six big-bore rifles among our group of nine, a trip that had taken on the air of a pleasure cruise less than 12 hours before suddenly becomes much more serious. I can hear it in the PH's whispers, and I'm glad for it. Getting here was fun, but now it's time to attend to the business of killing an animal that could just as easily kill me. Anton checks the wind while I chamber a .416 round into the Kimber, detach the sling and stuff it into my back pocket. Now we're hunting. "Stay close, in a line," he says softly. "You must be quiet." The sandy ground muffles our footsteps as we sneak through the yellowwood and mangosteen trees, helping us heed the PH's direction. We've gone about 200 yards with surprising silence and I'm wondering how long it will be until someone coughs or sneezes or rattles a branch, hoping it won't be me, when Anton suddenly drops to a crouch and brings his binocular to his eyes. A couple seconds later, I see it, too. A gray-black, square-like shape with rounded corners stands out against the island's palette of tan and green. With the help of 10X magnification I realize I am looking at the backside of a buffalo, complete with swishing tail, only to watch it disappear behind a screen of scraggly limbs. "Cow," whispers Anton. "Probably more very close." He points to a huge termite mound to our left that towers 20 feet above the island. "Let's go there and have a look." We stand in the shadow of the mound, smiling, excited, nervous. For several of us, including me, this is our first encounter with buffalo. After a long survey with the binocular, Anton reports the herd is scattered in the trees ahead of us. He will take me and three others-PH Dries Brönner and his son Reinhardt, who is filming the hunt, along with our tracker, Fabian-on the stalk, while the rest stay behind. I receive handshakes and quiet wishes of good luck, and a few minutes later I'm crouching next to Anton beneath the yellowwood in front of the termite mound, staring at group of a dozen buffalo lying in the shade 60 yards away. The herd has fed all night on the floodplain by the light of a waning full moon, and with their four-chambered stomachs full of grass, the buffalo are content to ruminate. They are in no hurry to move; everything they need is within sight. The same goes for us. I take a seat between the two PHs, leaning the weight of the rifle against my shoulder, and realize it was well worth a day's boat ride to be in this very spot.  More than an hour passes, and I have looked the group over well enough to know they are all cows and calves. I like Anton's style. He's patient, gathering intel about the herd and the landscape, planning possible routes that will get us closer, waiting for the buffalo to determine our next move. Three days ago he stopped a charge from an enraged cow elephant at a mere 6 yards with a single shot. This is a man who does not rush but takes decisive action at exactly the right moment.

More than an hour passes, and I have looked the group over well enough to know they are all cows and calves. I like Anton's style. He's patient, gathering intel about the herd and the landscape, planning possible routes that will get us closer, waiting for the buffalo to determine our next move. Three days ago he stopped a charge from an enraged cow elephant at a mere 6 yards with a single shot. This is a man who does not rush but takes decisive action at exactly the right moment.

That moment comes when a larger body moves through the shadows behind the cows. It's a bull and, by Anton's quick estimation, one worth pursuing. The cows, seemingly under the bull's command, rise and follow the brute to the left. We crawl to the right, doing our best to stay below the top of the sparse grass as we emerge from the yellowwood thicket. Our plan is to stalk into the herd from behind, the wind blowing across the buffalo's backs and into our faces. We move 40 yards, and then stop to glass for 20 minutes. Thirty more yards, 30 more minutes on the binos. It is now obvious the island is crawling with buffalo. We catch glimpses of the edge of the herd 50 yards ahead, slowly moving right to left through the dense brush. If we can reach a small hill 75 yards in the distance, we'll be in the middle of it and have a vantage point from which to find the bull. But our path is blocked. A scant 20 yards from the mangosteen we're kneeling under lies a cow with a calf. She's cloaked in shadow, mostly obscured by a fallen tree. The only thing that warns us of her presence is a twitching ear. I am at once tremendously grateful for flies. Had they not been bothering the buffalo, we may have stumbled right into her. The stalk would be ruined, or worse. Another cow with a calf joins the pair, and they move off together. I wipe the sweat from around my eyes and look at Anton. "Close," he says simply. We're about to get closer. The hill is surrounded by fan palm, and we crawl to its edge. Four feet high with broad, overlapping leaves, the palm hides our approach. It also hides the buffalo. We can hear them sloshing through the water just on the other side, but we can't see them. When I realize the low grumbling sound in my ears is coming from one of the buffalo's stomachs, I wonder with some alarm if we have gotten too close. Anton slowly rises from his knees to peer through a small void in the vegetation. I do the same, and immediately my vision is filled with black. The buffalo can't be more than 15 yards from us. Gripping my rifle, I feel very small as I return to the ground. Through the thumping of my heart I barely hear the small bull move away. Anton motions for me to stay put while he and Fabian slide on their stomachs along the border of the palm. They disappear behind a wall of brush, working their way up the hill. I have a few minutes to collect myself, and I think about what would happen if a buffalo decided to wander over to our side of the palm. I'm considering the possible outcomes when Fabian appears, rapidly motioning for me to join him. Three bulls are on the side of the hill, slightly below us, 25 yards away, Anton tells me when I squirm up next to him. The biggest, the one we saw more than two hours ago, is lying in the open. I steal a glance over the palms and quickly notice the bull has a wide boss with horns that curve deeply downward before sweeping back in wicked hooks. He's our boy, and I give Anton a nod. "When that bull stands," he says, "shoot him right in the shoulder. You'll have two seconds before he sees you and runs. Use the sticks." As I kneel beside the PH, he carefully raises the shooting sticks to form a tripod. When I stand behind them, I see the bull is already on his feet, staring in our direction. The rifle finds my cheek and the V formed by the sticks at the same time, and the safety goes off without me thinking about it. Even though the Weaver scope is set at 1X, it's full of buffalo. I direct the crosshair to that triangular-shaped area on the bull's shoulder I've studied in photographs for seven months. "Wait until he turns broadside," Anton whispers. Seconds seem like minutes. The bull knows something isn't right, but he's more curious than scared. He takes a half step, slightly turning his body toward the muzzle of my rifle. I don't remember pressing the trigger, but my shoulder rocks under the recoil of the .416. I chamber another round, recover, and see the bull is still on his feet, bucking and spinning in a cloud of dust. "Hit him again," Anton says firmly, the need for whispering now past. I step around the sticks, find the bull's shoulder in the scope, and send a 400-grain solid through his vitals. To my dismay, the bullet seems to have no immediate effect, and I work the bolt again. But as the cartridge reaches the chamber, the bull stumbles. There is no need for a third shot. Soon the villagers arrive via mokoro. They will feast for days on plentiful meat. They will take it by boat to their huts and cook it for their families. We celebrate a successful hunt, but later that night, motoring back up the Zambezi as its surface reflects a blood-red sunset, I have plenty of time to recall the tense moments of the stalk. At one point, we were surrounded as much by buffalo as by water. My boots are wet, but my mouth is still dry. A PLACE OF MAGNIFICENT SOLITUDE

Written by Anton Esterhuizen, Owner, Professional Hunter and Outfitter of Estreux Safaris

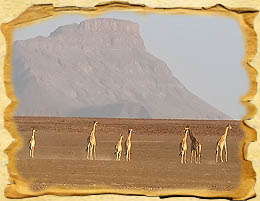

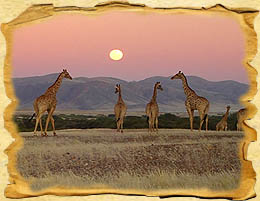

The Kaokoveld. A vast, isolated, arid and inhospitable piece of land in north-western Namibia. Large scale poaching and extreme drought during the early 1980's nearly wiped out its rich wildlife, but unconventional ideas, that challenged the conservation thinking of the day, made sure that the Kaokoveld regained, to become one of the few conservation success stories in recent history. Today, this is one of the last remaining true wilderness areas in Africa. The Kaokoveld is a landscape of vast untouched gravel plains, littered with the debris of ancient lava flows, large mountain ranges with sheer cliffs, and endless scree slopes. Rain is a rarity and most years the surface lies barren in the baking sun, exposed to the searing desert winds. Sometimes however, dense coastal fog is driven in from the cold Benguela Current in the west and provides an aura of mystery and impenetrability. This barren landscape however undergo a total transformation during the evening when the light goes dimmer and change the bleak, seemingly lifeless landscape in soft shades of purple and blue. Ephemeral rivers draining westwards towards the cold Atlantic Ocean provide vital lifelines for wildlife in this desert environment. Transverse rock barriers force water to the surface, creating permanent and semi-permanent waterholes for desert wildlife. These linear oases serves as a major source of food and water for springbok, oryx, giraffe, elephant, black rhino and other resident game from the plains and mountains nearby. Necessarily, lion, leopard, hyena and cheetah patrol these rivers. My first visit to the Kaokoveld was with my late father, back in the early 1970's as a young boy. The absolute vastness, extraordinary beauty and diversity of the landscape captivated my imagination. Its remoteness and untouched nature left a lifelong impression on me, but it wasn't until the late 1990's that I got a change to revisit the Kaokoveld and also provided the privileged to work in this awe-inspiring area together with my young wife. To me this was a dream comes true. Based at a very remote base station called Wêreldsend, (Worlds end) I conducted many patrols and safaris into this land collectively (former Damaraland and Kaokoland) known as the Kaokoveld. With my wife, I made a point of getting to know the area like few other white men, have ever got to knew it. I drove every road, track and trail. Foot patrols was at the order of the day with the local inhabitants of the area, the semi-nomadic Himba; one of the last remaining tribes in Namibia keeping true to their tradition and culture. They showed us springs and water sources, no person could imagine existed. Employing ex-poachers as game guards seemed to be paying off, as poaching become non-existent in some areas, with only a few isolated cases of subsistence poaching remaining. The game started to bounce back at almost an alarming rate.

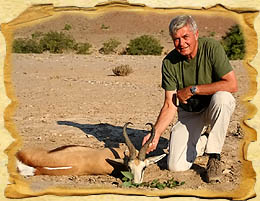

Game counts were initiated and over the years an upward trend was clearly noticeable on game numbers. The newly introduced conservancy legislation in 1996, endorsed by the Government of Namibia, started paying dividends in terms of communities now looking after their wildlife and could benefit from it through Trophy hunting, Lodge Joint-Venture establishments, Community-run campsites and Employment of members of the conservancies. I first started hunting in the Kaokoveld in 1999. Over the next couple of years, I introduced many hunters to the area as well as Professional Hunting Outfitters, but it wasn't until 2008 my own Outfit, Estreux Safaris, signed a three year contract with the conservancies of Puros, Orupembe, Sanitatas and Marienfluss. I brought in only a few hunters every year. I've never been interested in large quantities of hunters and for that matter trophies, but always strived to give each and every hunter a true hunting experience. Shooting the best possible trophy, old, long and thick, I could produce ethically under the principles of fair chase, has, and will always be my motto. Visiting one of my hunting clients in Kitzbuhel in Austria recently, I looked at his Springbok on the wall and remembered the hunt. He booked a 16-day hunt/tour combination in the Kaokoveld. "Anton" he said; "I want an exceptional Springbok, nothing else". I picked him up from the airport on my birthday, July 14th, and we drove the next day to the Kaokoveld. We sighted his rifle close to the small village of Sesfontein and slept in the bush that evening. The next day saw us arriving at the Himba settlement of Puros. With a game guard from Puros conservancy we started hunting the large plains north of Puros. We shot an old broken horn Oryx male for meat, as the conservancy had a meeting the next day and requested us to shoot something for the pot. We hunted hard the next couple of days and probably saw close to 300 Springbok. Big rams were at the order of the day, but my client wanted something really special and we had enough days. One afternoon late we walked up a dry riverbed, actually looking for an Ostrich, when my eye caught a glimpse of a Springbok ram grazing away from us, disappearing behind a Mustard bush. Not sure how good he was I started stalking it. The ram however disappeared and we returned to camp that evening. Camping under huge Camelthorn trees gave a sense of the Africa of the past. Totally at peace around the campfire we listened to the sounds of barking geckos just after sunset and the eerie sound of a howling jackal. The next day saw us back in the river searching for the ram. It was not till late that afternoon that we eventually located the ram grazing slowly from the plains towards the river. Favored by the wind we took up position right in its anticipated path towards the river. I could see his was big, but needed him to come closer to really judge the trophy well. After what seemed like an eternity the ram was a hundred meters away and I just new without even using my binoculars that this was the ram we were looking for. The ram collapsed on the spot with a .300 Ultra Mag. bullet placed neatly on the shoulder. Touching the horns I realized why I love to hunt these magnificent animals. Perfectly adapted to this dry environment, I am always reminded at how unique God have created his creatures.

Driving back to camp that evening I stopped and got out of the vehicle. I listened to the silence, looked at the soft colors on the mountains in the last rays of the sun and appreciated this place of Magnificent Solitude called the Kaokoveld. DROUGHT AND "PROBLEM" ELEPHANTS

Written by Anton Esterhuizen, Owner, Professional Hunter and Outfitter of Estreux Safaris

Damaraland, North West Namibia, September, 1991. The north west of Namibia experienced one of its driest periods ever. Rain is an absolute luxury and for the past five years the area has had virtually no rain. Livestock and wildlife were dying. Most boreholes and springs dried up long ago. This was desperate times for most of Damaraland's wildlife. Elephant however went back on their ancient routes to the east, re-discovering old known waterholes, springs and food. This however brought them into conflict with commercial farmers, struggling desperately to keep afloat with their deteriorating livestock and dwindling water resources. "Your animals are causing trouble again. Either you remove them or I will do it for you. The bull has destroyed my major water tank. You have 24 hours" The telephone went dead before I could say anything, but I knew exactly who it was. As I slowly put the telephone down, I realize that we had to do something to regain our credibility with the farmers, and make them more tolerant towards elephant. I was a young Warden, working for the then Department of Nature Conservation, and one of my responsibilities were problem animal control, in this case, elephant. I knew the problems well as I have been dealing with these particular elephants for quite a while. Every time we push them back from the commercial farming areas towards the communal areas where they come from, but the lack of food and water drove them back after a while. I wrote my report and add a couple of my previous reports to make my case stronger to my superiors. The answer came back almost immediately. Approval has been granted. I must shoot the bull from the herd causing the problems. I grab my bedroll some food and most importantly my .416 Rigby. Although an old gun, it shot straight, was very reliable and got me out of many a tricky situation in the past. It took me most of the day to get to the farm, where I was greeted by a very angry farmer. I kept my cool and let him blew off steam. After I have patiently listened to all the stories I have heard so many times before, I showed him the approval to shoot one elephant bull. "O" he said. "Why didn't you say so in the first place" I just grinned and told him I'll be sleeping near one of his waterholes that evening. I always enjoyed working in this area, as it is predominantly Mopane Savanna, interspersed with granite kopjes (small hills), and occasionally breaking up into areas with small plains. If no cattle were around, these plains were good areas to find fairly large herds of oryx/gemsbok, springbok and a good population of kudu early morning and late afternoon. Towards the west the kopjes made way for large rolling mountains. Elephant, oryx, Hartmann mountain zebra, kudu and even giraffe could be found on the slopes. One of Namibia's largest ephemeral rivers, the Huab River made its way through this area, providing a vital lifeline to man and animal alike, in this semi-desert environment. The drought however left its mark. There was virtually no grass left and shrub Mopane looked none better with mostly brown leaves and here and there a sign of new leaf growth. There was however the promise of an early rain showers in the air. This however pushed the temperatures to well above the 40 degrees Celsius. After a simple dinner I sat at the fire looking at the Mopane wood embers. In Africa they call it Bushman TV. Apart from a lonely Pearl spotted owl's call, it was silent. The way I like it in the bush. The stars however were so bright; it felt as though I could touch them. It was a pretty uneventful evening with no elephant showing up. I drove most of the roads the next day to find fresh tracks. As sunset approaches and the last rays turned the land in soft shades of orange, purple and pink I found myself back at the same waterhole. No fresh tracks the whole day. I turned in early and the next morning as the sun appear on the horizon I found myself at the top of one of the highest mountains in the area. As it is very dry I am able to see virtually everything below me. After a couple of hours I returned to my vehicle and drove to the neighboring farm in the hope of finding fresh tracks. My early wake-up call delivered little to nothing. The days come and go, but the elephants seemed to sense that something was in the air. I got reports from different areas of elephant, but it was all in areas where they can do very little harm. It became a waiting game, as I must shoot the bull on the farms where the herd causes damage. The farmer in the mean time got increasingly upset as he wants to see a dead elephant. He had no more damage from elephant due to their absence and that settled the issue for now. After a week I left the area and returned to my office. No elephants, no work for me. I knew it was just a matter of time before I would be called to shoot the bull, and three days later I received the call. "The elephants are back" I left immediately and arrived at the farm a couple of hours later. It was 15h00 and unbelievably hot. I picked up the tracks immediately and started following them. The tracks are from the previous evening and the dung has already developed a hard outer surface. They are heading for the mountains and I pick up the pace as best I can while following the tracks and also looking out for them. To my dismay they start turning east. Downwind. The sun was nearly gone. I ran up one of the kopjes desperately to see them. Nothing, but I had a pretty good idea where they were going. The next day I left the tracks and took a short cut over the mountains, to an isolated water I knew about. I picked up the fresh tracks of the group almost immediately. I recognized the bull's big feet with the distinct cracks in it, I by now, knew so well. The wind however is very bad and following them will be plain stupid with this wind. They will smell me long before I can even see them. I followed the tracks in the gorge till I was sure where I though they intend to go and then left the tracks. They were now entering huge mountains, although staying in the gorge below. A couple of kilometers further I knew the mountains would open up and then it would be nearly impossible to follow them with the current wind. I had one option and that was to go up the mountain as high as I can and to get in front of them. I will then wait to shoot the bull when they exit the gorge. All good in theory I thought. As long as they were feeding I had a small change to catch up with them, and even pass them. I ran as fast as the rocks would permit me, trying desperately to make as little noise as possible. I was still running, when I came to an abrupt halt. The elephants were no more than 300 meters below me, and listening, trunks in the air. I stood motionless looking for the bull with my binoculars. I knew they couldn't smell me, but they definitely heard me running on the rocks. The bull was at the back, a little bit separated from the group. It did not have great tusks, but it was an old big bodied elephant. They started feeding again and I move forward without a sound as quick as I could. We were nearly at the end of the gorge. I positioned myself right in their path. The wind was fairly steady by now, and being almost mid day I knew that the wind could change any time. The elephants however were looking for a resting place. Siesta time. There were some fairly large trees a couple of hundred meters away. The whole group moved pass me and came to rest underneath the big trees. The bull however hanged back, and chosen a lonely Mopane tree further away to come to rest. I watched it a while and then decided to move in on the bull. It was pretty open country with a few shrub Mopane. I stalked the bull to within 15 meters, when he decided to started moving again. I was in the perfect spot for a side brain shot from the left. I lifted my rifle, and draw an imaginary line from the middle of the ear-slit to the eye. I can see the cheek bone clearly, and about four fingers in front of the ear-slit on the imaginary line to the eye above the cheekbone the bead came to rest. I can see the puff of dust, the solid sound of the bullet as it finds its target. The hind quarters gave way and the head and trunk swing skywards. The head has hardly hit the ground when I put in the "coup de grace'. It all happened in less than three seconds. I am vaguely aware of the back leg still kicking, an indication of a brain shot, when I swing around towards the herd. I lowered my rifle. Of the herd I can only hear branches breaking as they are bursting through the small shrub Mopane. As the dust settles it became very quite. I hardly feel the sun burning down on me with all its intensity. I even less noticed the thirst.

As I look at this magnificent animal lying in front of my feet I can only admire it. Although shot as a problem animal, I have hunted it ethically, on foot with a good clean shot; the only way to hunt these magnificent animals. WHEN NIGHT FALLS IN AFRICA

Written by Wanda Esterhuizen, Owner of Estreux Safaris

I was fortunate and blessed to grow up in the field and on a farm in South-West Africa then, better known as Namibia now. But it was only later on in my life that I met someone that taught me how to use a rifle and today after twenty years we still share the same passion - hunting and conservation. My husband and I lived in the desert for 10 years. We've travelled the whole Damaraland and Kaokoland every single day, for 10 years. It was during this time that I've realized how amazingly God created earth. So fragile, but yet, He gave it to us humans, to take care of. During this period in my life we would night after night slept under the African stars, something that the less fortunate ones living in cities, only dreams of. We don't suffer from light or air pollution. Only crystal clear skies. My husband and I would lie on our backs watching the starts and satellites passing by at night; though sometimes it felt as if one could catch a shooting star. Just before I went to bed I would put an extra few sticks on the fire; it made me feel more secure while the campfire was burning. It is strange how one would be talkative while the sun is setting in the west and the campfire burning. Watching the flames of the campfire while we enjoy supper, I really do appreciate and enjoy the sounds of the night. It varies from an owl, elephant, hippo, jackal, hyena or even lion. I remember clearly the very first time, many years ago, I heard a lion roaring, what felt to me very close, but my loving husband put me to ease and ensured me that it was actually very far away. Needless to say, I didn't sleep that night. We prefer not to sleep in a tent; we sleep under the bright stars, and breathe the fresh air. Once the campfire burned out and its pitch black, only the stars above that shines a light onto us, I tend to feel less secure when a twig or branch breaks within hearing distance from you. For me there's something magical about a burning campfire. My husband and I have, according to me, one the most beautiful hunting concessions in Namibia, the North-western part of Kaokoland. We meet so many different people/hunters, our guests, from all over the world. My husband believes in true ethical hunting on foot. They would return from the field after a hard day of hunting sometimes in unbearable heat. After a hot shower the guests would come and sit around the campfire, where most cooking takes place. I enjoy watching how easily they relax by simply staring at the fire with a cold drink in hand. The guests will share hunting stories with each other, like only men can do. Strangely enough while the fire is burning there's talk and laughter and no one minds  about the sounds of the night, but once the fire goes out and the sound of a Hyena, Hippo or lion echoes into the night, I've seen huge, big, grown-up men looking over their shoulders staring into the dark and immediately starts to whisper. My husband will immediately explain to the guests what the sounds were; he is so truly blessed with a magnificent knowledge of wildlife and nature; what a privilege to live with someone like that. To me, that is what I call to be rich, not money wise, but by experience and to fight for what you believes in.

about the sounds of the night, but once the fire goes out and the sound of a Hyena, Hippo or lion echoes into the night, I've seen huge, big, grown-up men looking over their shoulders staring into the dark and immediately starts to whisper. My husband will immediately explain to the guests what the sounds were; he is so truly blessed with a magnificent knowledge of wildlife and nature; what a privilege to live with someone like that. To me, that is what I call to be rich, not money wise, but by experience and to fight for what you believes in.

After many years of marriage, the doctors informed us that we will not be able to have kids of our own. Anton and myself looked at each other and said to the doctor that we believe that we will have kids of our own one day; well in 2007 our dream came true when our own daughter were born. Today, after 5 ½ years we all share the same passion - hunting and conservation. The legacy continuous. Our daughter, always bare foot, enjoys the true nature that only this specific hunting concession of ours can offer. Now my daughter will help me build a fire every night before the hunters arrives back in camp.

After many years of marriage, the doctors informed us that we will not be able to have kids of our own. Anton and myself looked at each other and said to the doctor that we believe that we will have kids of our own one day; well in 2007 our dream came true when our own daughter were born. Today, after 5 ½ years we all share the same passion - hunting and conservation. The legacy continuous. Our daughter, always bare foot, enjoys the true nature that only this specific hunting concession of ours can offer. Now my daughter will help me build a fire every night before the hunters arrives back in camp.To be in the nature makes you humble and thankful for what you have, you forget about the everyday rush and negative things in live. Out in the field, without electricity, telephones or televisions, you have time for each other and most importantly you have time for your children. What a blessing Our bank, Standard bank Namibia, have a slogan called "they call it Africa, we call it home". Next to a campfire, under African skies, I feel at home. Guests might call it Africa, we call it home. THE EYES IN THE BUSH THAT WATCHES YOU …WHILE YOU ARE HUNTING

Written by Wanda Esterhuizen, Owner of Estreux Safaris

Mid August in Kaokoland, Namibia is extremely and sometimes unbearable hot. We hardly received any rain this year in our hunting concession. Most of the game has moved in an easterly direction to find better grass and water. Our client, an Austrian by birth *Stephan, turned out to be a very relaxed, true gentleman, who has hunted all over the world before. He only speaks when needed, but always friendly. His passion - HUNTING! He came to hunt leopard. My husband has put up bait long before *Stephan arrived. Signs of leopard activities around the baits seemed very positive, and we knew that we will have a good chance of getting the leopard. All hopes were up. This client had two requests; firstly, to hunt with my husband and only my husband and; secondly, he only came to shoot a leopard and nothing else. Typically of my dear husband, he had taken out a trophy permit as well ("just for incase" he said). Stephan's flight were delayed and we had to sleep over in Otjiwarongo. We left early the next morning for our hunting destination up in Kaokoland, a 10 hour drive. As we came closer to our end destination the scenery changes drastically, breathtaking beautiful. Stephan was speechless and asked a number of times for my husband to stop the vehicle for a smoke break. He just simply couldn't believe that we have this endless amount of land specifically between Sesfontein and Puros where no/hardly any human is living, only animals roam there. We arrived at our hunting camp late afternoon. While we were unpacking our vehicle, Stephan took the opportunity to explore around the camp with an ice cold Namibian beer in one hand and his camera in the other. After a while he came back into camp and told us that at first when he heard about the long 10 hour drive to our hunting concession he wasn't keen about the idea of sitting so long in a vehicle with people you've just met, but he said the scenery on the way to our end destination made up for it. He looked over his shoulder into the sunset and said:" but this is magnificent, just look at sun just going down behind the dunes". We've nodded, and I immediately thought about those people living in cities with all kinds of pollution and here we stand watching the sunset and just a few meters away from us a few springbok grazing. What a privilege. The first morning the men went out very early as my husband wants to show the area to our client and check on the baits as well. When they arrived back in camp later, all Stephan could talk about was the quality and variety of animals. He mentioned that he's glad that Anton had taken out a trophy permit as well. The men set off again in search for leopard. As the days gone by, Stephan had shot a few trophy animals, and was pleased. He just simply couldn't wait to share these memories with this wife and kids. One concern Anton had, was the fact that there were quit a number of lions in the area and they found fresh tracks every time around the baits. It did however bring back memories to me of an incident that occurred in June 1997 when Anton was still employed with the Ministry of Environment and Tourism. He was with a team doing research on lion movements in Caprivi and was nearly killed during this time by a male lion. The afternoon of the second last day, while I was preparing dinner in camp, I suddenly experience a feeling that something somewhere is wrong. I ran outside to look for my daughter, who I found playing in the sand. I looked at my watch, 18h20. One of our workers came by and asked me what is wrong. I told him that I'm worried about Anton and Stephan. He tried to reassure me by saying that I don't have to worry about them and that Anton will be fine, "Mr. Anton is a good hunter, he respects nature so nature will respect him" he said. I walked back to finish the food. I started praying for protection for Anton and Stephan. About an hour later I heard the vehicle and felt a relieved. They arrived back in camp, but both just sat in the vehicle, no talking, just staring. I went out and opened the door of my husband. I realized something had happened by the look on his face. I was shaking and scared. My husband got out of the vehicle and hugged me so hard that it felt as if I couldn't breathe. I asked him what is wrong but said that he will tell me later, he walked off to our tent and I couldn't help feeling sorry for him. Stephan climbed out of the vehicle and light a cigarette. He went and sat at the table, I offered him a beer and when he took the glass from me I realized that his hands were shaking. He said:" Wanda, we are lucky to be here; if it wasn't for your husband's knowledge and experience today then we would've been dead, eaten by lions. At 18h20 this afternoon we were sitting in the blind waiting for the leopard to come in. We heard a francolin making a noise and suddenly it was quite. The expression on Anton's face made me aware that he's not at ease, he showed me to be quite. I thought it was only a francolin, but obviously not. I felt save with Anton because I realized that he's aware of things going on around him. The next minute, from nowhere, a lioness walked past right in front of the blind, heading for the bait. Again, Anton showed me to be quite. I felt uncomfortable, because when I saw the lioness I immediately started sweating. Suddenly, Anton slowly picked up his rifle as well (I had mine ready pointing towards the bait waiting for the leopard to make its appearance). The next minute, a male lion stood right outside the blind, trying to get his foot underneath the blind. Wanda, he was so close to the blind, if I had a pencil I could've sketch him on the canvas material of the blind. It felt like hours, and both of us realized that we will not be able to get out of the blind while the lions were around. It felt like an eternity, and I was soaking wet from my own sweat, scared that the lions will smell me. I still don't know what happened but all of a sudden the lions disappeared (I knew what it was, thank you Lord). We got out of the blind, Anton first. He said that we better get to the vehicle, parked about 800 meters from the blind. I wanted to light a cigarette for the nervous, but the look on Anton's face told me to rather leave the cigarette. As we were getting closer to the vehicle we both heard something and realized that it is the lions behind us. We got into the vehicle and Anton switched the vehicle and lights on, the lions were only a few feet from us. This was the scariest moment of my life, but this memory I want to treasure as long as I can. I want to come back next year for the leopard".

Stephan told us on the way to the airport that this hunt exceeded all expectations, even though he did not get his leopard. We share the same passion - HUNTING. Even if you don't shoot an animal, you need to take a "story to tell" back home. KING OF THE MOUNTAINS

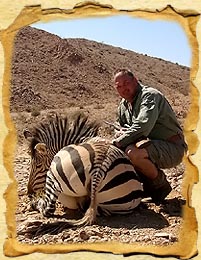

Rain during the 2007 rainy season was extremely poor in most of Namibia, but even more so in the Puros Conservancy in north-western Namibia. This arid semi desert environment, with its endless plains, rugged mountains, sparse vegetation, well known Hoarusib River and Himba pastoralist forms part of the greater Kunene region, formerly known as Kaokoland. Hartmann's Mountain Zebra, one of Namibia's endemic species and listed on Cites 11, remains one of the most sought after trophies and exciting hunts Namibia can offer. This is especially true in the far north west of the country where they occur naturally and can still roam free, without the hindrance of fences. Hunting Hartmann's Mountain Zebra on foot in Namibia's communal conservancies in north-western Namibia is demanding, a great challenge and truly exciting. This, Andrew Kayser from South Africa found out, while on a hunting trip in the Puros Conservancy during the 2007 hunting season. I agree to meet Andrew at Wêreldsend, IRDNC's base camp, 60kms east of Torra Bay. A big man with an even bigger smile, and a small heart as I've later found out, wriggle his body out of the vehicle. Passionate about hunting and also chairman of Tembo Hunting Branch in South Africa, he booked for a community hunt in Puros, but also Hartmann Mountain Zebra as trophy. We left Wêreldsend on a chilly morning in early June for the six-hour drive to Puros. After checking and shooting his rifle we decided to walk the dry mountains north west of Puros village. With a strong cold west wind in our faces, accompanied by the Puros conservancy field officer, we carefully search the mountains and gullies for any sign of life. As it is our first day we are not in a hurry, and enjoy being out in the field after the long drive. The grass is sparse to non existent and we only found a few oryx tracks leading down to the lush green Hoarusib River; A true oasis in this harsh landscape, where they can found some greenery and water, but also the danger of two semi-permanent female lions always on the lookout for any sign of weakness! Early the next morning we found ourselves in the Okongue area south east of Puros on a vantage point, high above the plains where the first stripes of golden sun, colour the bare isolated rocks and grey lifeless soil into a warm blanket. Patches of grass, left from the exceptional rains Namibia received during 2006 can still be found, although few and far between. This area has been earmarked by the conservancy as an exclusive wildlife and hunting zone. It is bitterly cold, and we found it hard to steady our binoculars. We scan the mountains and valleys, as the zebra will start moving back into the mountains after their nightly parade down in the plains. We eventually locate a family group of seven zebra at the foot of some distant mountains. "Here you can see to eternity," remarks Andrew dryly as the zebra seems like an eternity away from us. There is no wind and we approach them carefully from the west as the wind normally blows from the east early morning. Oryx can be seen scattered over the plains as mere dots. Two ostriches are keeping us carefully under surveillance from a distance and start moving slowly away from us. Coming over the ridge the zebra is still 400 meters away with no cover in between. We are also slightly above them. They are grazing and haven't noticed us yet. As there are oryx to our left and right we can do very little, but to get comfortable and hope they move towards us. In the mean time we identified two stallions, one older than the other. Unfortunately the wind picks up and as usual starts playing games in the mountains. The zebra immediately smelled us and first started moving towards us, then recognizing their mistake, fled up the mountain to our utter dismay and disappears over the ridge. Andrew jumped up and suggests we move around and cut them off. I know it's useless as Hartmann zebra is the undisputed king of the mountains and hunting them earlier in my career as an inexperienced hunter, many a times had to return tail between the legs as they seem to get wings on their feet. I decided to keep quite and let Andrew experience the grace of these wonderful animals. We rush up the mountain huffing and puffing. Andrew dragging his 120 plus kilogram carcass up the mountain. On the other side he was amazed at the light footedness with which the zebra moved in the mountains, as they were already hundreds of meters away from us. I just chuckled softly and suggested we look for other game and come back the next day as the wind by now was very bad. We left at five 'o clock the following morning armed with thick jackets, rifle and binoculars. There is a strong easterly wind, which cuts into the bone as we make our way up a mountain west of the Okongue plains. As the sun rises over the horizon, dust clouds in the river below draw our attention to three zebra taking a dust bath. A stallion and two mares. A family group started there ascend from the valley below into the mountains and disappear. As the three zebra seems peaceful, we sat quietly just watching them for a while. An oryx appeared on our right looking in our direction and satisfied of no danger slowly feeding away from us. Springbok down in the valley stands quietly trying to catch the first warmth of sunlight. We start our stalk down a gully out of sight of the zebra and then up river towards them. As we move slowly forward making use of every available cover and shadow to hide ourselves we almost walked into a kudu bull. We wait for it to move off and then continued our stalk. The sun by now shines with all its ferocity and it's hard to believe that it was so cold earlier. The wind is also not doing anything to make the stalk easier and changes more often than my wife clothes. The zebra have in the mean time decided to move out of the river and were now feeding half-way up the mountain. We had a great dilemma as very little cover were available between us and the zebra, making a stalk virtually impossible as well as the fact that they were above us. "Did we waste too much time on the stalk up to this point" I was wondering by myself contemplating various ways as to get within shooting range of the zebra. Making use of milk bush (Euphorbia Damarana) as cover we crawl inch by inch towards the zebra; look, crawl, wait, look, crawl, wait, trying to be as quite as possible on the loose stones and steep gradient. Apart from the stones cutting into bare flesh, as we are wearing  shorts, it feels as if the stones get a couple of degrees hotter with every inch. Looking back at Andrew to see how he is doing, I stalled. An oryx are looking straight at us from no more than 30 meters. It just appeared from nowhere. "Stay very still," I hissed to Andrew. "What?" "Stay very still," I hissed again, this time rolling my eyes towards the oryx, still watching us. Why do animals always have this cunning ability of catching you in the most awkward position when you cannot afford to move? After staring us down, satisfied that we have endured enough pain in our limbs and back, he trotted off. We waited for a while and then dare to look if the zebra were still there. We only see two, the third, our stallion, is gone. I scan the mountain, which by know is all shades of grey and white in the blinding sun, making it extremely difficult to see zebra, believe it or not. Andrew and I are lying next to a milk bush, trying to make use of its limited shade for cover. By now there is no wind and old spikes have no sympathy for us. I am still scanning the area for the stallion when he suddenly appears from behind a bush and rejoins the other two. Whispering the position of the stallion to Andrew, we waste no time in getting him in position to shoot. Although still 150 meters away, Andrew feels comfortable he can take the shot and so do I. Leopard crawling inch by inch forward, Andrew moves at a snails pace to get into position, very aware that one miscalculated move can cost him his zebra. I watch anxiously from the back alternating my attention between Andrew and the zebra. At once the stallion picks up his head and I can see his nostrils opening wide. Without taking the binoculars away from my eyes I look at Andrew and see with relief he is in position and is about to shoot. As the shot rang out I see the bullet finding its target, as the stallion starts running down hill. Eighty meters and it went down.

shorts, it feels as if the stones get a couple of degrees hotter with every inch. Looking back at Andrew to see how he is doing, I stalled. An oryx are looking straight at us from no more than 30 meters. It just appeared from nowhere. "Stay very still," I hissed to Andrew. "What?" "Stay very still," I hissed again, this time rolling my eyes towards the oryx, still watching us. Why do animals always have this cunning ability of catching you in the most awkward position when you cannot afford to move? After staring us down, satisfied that we have endured enough pain in our limbs and back, he trotted off. We waited for a while and then dare to look if the zebra were still there. We only see two, the third, our stallion, is gone. I scan the mountain, which by know is all shades of grey and white in the blinding sun, making it extremely difficult to see zebra, believe it or not. Andrew and I are lying next to a milk bush, trying to make use of its limited shade for cover. By now there is no wind and old spikes have no sympathy for us. I am still scanning the area for the stallion when he suddenly appears from behind a bush and rejoins the other two. Whispering the position of the stallion to Andrew, we waste no time in getting him in position to shoot. Although still 150 meters away, Andrew feels comfortable he can take the shot and so do I. Leopard crawling inch by inch forward, Andrew moves at a snails pace to get into position, very aware that one miscalculated move can cost him his zebra. I watch anxiously from the back alternating my attention between Andrew and the zebra. At once the stallion picks up his head and I can see his nostrils opening wide. Without taking the binoculars away from my eyes I look at Andrew and see with relief he is in position and is about to shoot. As the shot rang out I see the bullet finding its target, as the stallion starts running down hill. Eighty meters and it went down.

That night there were great festivities at Puros as zebra meat found their way into grateful Himba stomachs, washed down with Carling Black Label beer. And for Andrew, apart from some cuts and bruises! A Namibian dream comes true. The satisfaction of hunting the King of the Mountains on foot in its natural environment. Written by Anton Esterhuizen for the Africa du Süd advertising Magazine A NAMIBIAN ALTERNATIVE TO TROPHY HUNTING

I am a PH registered for 'Big Game' with NAPHA and Natural Resource Management Coordinator, Kunene Region, for a Namibian NGO, Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation. IRDNC pioneered community-based natural resource management in the country and now provides technical, financial and logistic support to more than 40 of Namibia's 75 registered or emerging communal area conservancies. This successful national program, linking wildlife and other natural resource conservation to rural development, has won a number of international awards and 14 communal conservancies are already earning more than their own management costs. More than 10 million hectares has been voluntarily put under conservancy status by rural communities, hundreds of new jobs have been created in remote areas and in 2005 more than N$8 million flowed directly into conservancies with another N$20 million earned indirectly. Testing new ideas to generate conservancy income is a major focus for IRDNC. One of my roles is facilitating trophy-hunting contracts in conservancies and in the past two years we have also successfully tested a pilot project called Premium Hunting. This is basically a wildlife management culling exercise that nonetheless offers all the ingredients of hunting - except the trophy - at a much-reduced price. This Namibian Professional Hunters Association-supported project, based on quotas established by the Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) and the relevant conservancy committee, allows 'premium' hunters to shoot more than the traditional trophy hunting permit limit of two specimens. But the only trophy is a photograph. No part of the animal is taken out of the area by the hunter and the entire carcass is the property of the conservancy. Because no trophies are involved a licensed PH is not required although the project has trained local guides.  This is NOT trophy hunting at a cheap price but rather an alternative to trophy hunting for 'real' hunters who are fit and enjoy the challenges of hunting the desert on foot.

This is NOT trophy hunting at a cheap price but rather an alternative to trophy hunting for 'real' hunters who are fit and enjoy the challenges of hunting the desert on foot.

Because hunters must be fully self-sufficient, most clients have so far come from Southern Africa. But we are planning several rustic camps, owned and operated by conservancies themselves, to accommodate overseas hunters. In our first year, 2004, we had one client who took 12 animals and generated N$8 000 for the members of Puros Conservancy. In 2005 we had three hunters who took 30 animals, earning two conservancies N$26 000. For 2006 six hunters have booked so far and interest is growing in both the German and Italian markets. This may not sound a lot of money but this is a trial period, with hunters taking home their photographs and memories of a tough and authentic African hunting experience in a spectacular, remote desert environment. Meanwhile, the conservancy has the benefit of the game meat, the income from selling the skins and horns and the cash earned by local guides and at no cost the conservancy has culled its surplus game that competes with its members' domestic stock. For more information on this innovative alternative to trophy hunting, please contact Premium Hunting, c/o Anton Esterhuizen (Estreux Safaris) at IRDNC (E-mail estreux.safaris@mail.na) who does Premium Hunting within conservancies. An article written by Anton Esterhuizen which appeared in African Sporting Gazette (Nowadays African Hunting Magazine) magazine, Botswana Feature, Volume 12, Issue 2, Oct/Nov/Dec 2006, Page 8. NEVER SHY OF HARD WORK - PROFILE OF ANTON ESTERHUIZEN

Antonie Esterhuizen, head of IRDNC's natural resource management support unit for 28 Kunene conservancies, is a passionate conservationist and a professional hunter committed to seeing both people and wildlife thrive in Namibia's communal areas. It was the practical combining of these elements that won him the 2006 Namibia Professional Hunter Association's "Conservationist of the Year award". Anton has facilitated and assisted a number of communal area conservancies to enter into fair trophy hunting contracts with professional hunters and he has taken the lead in pioneering an innovative form of local conservancy hunting in which a communal conservancy sells some of the game from its own-use quota to hunters on a permit system. Appealing to the fit, 'adventure' hunter, such hunting takes place on foot in rugged terrain, with conservancy game guards and a professional hunter. The hunters take away only their photographs and conservancy members receive the meat, plus the per-animal fee. He worked closely with NAPHA to facilitate the training of four conservancy trackers as hunting guides and two more are being trained by him. Anton's contribution to Namibia's national community-based natural resource management program goes beyond hunting, however. He is responsible, with MET, for training conservancy staff in wildlife management and he assists conservancies to develop management plans. Working with conservancies and MET to develop and implement problem animal management strategies is another key focal area. He joined MET in 1988 and after obtaining a National Diploma in Nature Conservation from Polytechnic of Namibia (and being the best first year student of his year), he built up experience in a variety of posts across the country. In 1996 he was appointed Chief Control Warden for North East Namibia. This put him in overall charge of 12 million hectares of North East Namibia - Mahango Game Park, Kaudum Game Park, West Caprivi Game Park, Mangetti Game Camp, Mamili National Park, Mudumu National Park, East Caprivi, Kavango, Grootfontein and Tsumeb Districts as well as former Bushmanland. In 1999 Anton and his wife Wanda joined IRDNC and moved to the NGO's central Kunene base at Wêreldsend. In 2001 he obtained a pilot's license, qualifying as the best student of his course.

Last year he represented IRDNC at an international symposium on leisure hunting, jointly organized by IUCN and the Zoological Society of London in the United Kingdom. The symposium's title is 'Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice'. A quiet and serious person who is at home in nature and who is never shy of hard work, Anton has reason to be proud of his ongoing contribution to the conservancy program - a program which earned conservancies more than N$60 million in direct income and which has created hundreds of new jobs in remote rural areas. It also has significantly expanded the range and safety of many of Namibia's wild species including elephant, rhino, lion, cheetah, leopard, kudu, gemsbok, giraffe, zebra, springbok, eland, buffalo, eland, tsessebe and more. An article written by Dr. Margaret Jacobsohn, which appeared in the Conservation Magazine CHOOSING HEAVEN

(For Mr. Anton Esterhuizen) The Cites Convention has declared Panthera Leo (the lion) on one of its schedules, enforcing more protection for their diminishing population. Their biggest threat in Namibia is the loss, or shrinking, gene pool. If only one lion remains that is immune to a specific disease, and that lion is killed, this gene strain will have been removed forever. The Cites declaration offered new hope, a new ray of life for the lion. It was July and three of us set off from Katima Malilu to Mamili National Park. I was the Chief Control Warden of the Northeast Parks in Namibia. Some of my rangers had informed me of a pride of lions that had moved into Mamili, the land of the African Buffalo. The Chief Warden of the Caprivi Parks and a biologist accompanied me as we set out to dart lions in the area. We would tranquilize an entire pride, take blood samples, and examine their teeth in an effort to measure their overall health and physical condition. The decrease in lion population had been attributed to increased exposure to humans. Although there had been extensive research conducted on lions in Namibia, the decrease in population gave due reason for concern. We were all well aware of the importance of accurate data and we were fuelled with the desire assist in maintaining our lion population. We arrived in the Park with high hopes and after a brief discussion with our resident Rangers we learned that there were nine lions in the pride. Their location was just ten kilometers north of the station. Even our Rangers feared the lion, for he is the ruler of this land. Rarely can even man's modern weaponry match the lion's power as his communion with the land enables him to outwit and outmaneuver even the most skilled hunters. July is well after our rainy season, but water is plentiful and the grass is high due to the river rising from the floods originating in Angola. Huge herds of game migrate from the Okavango Delta. They are drawn to the lush, green grass and the lion prides are never far behind. These lions were quite exceptional in my eyes because they were renowned buffalo hunters. They are kings in their own land, afraid of nothing and will defend in the most compromising situations. By midday we arrived at a V-shaped bend at the river. The thatching grass stood tall and elephant grass waved and danced in the wind. This was Mamili. Flood plains and very tall grass characterized this terrain - here the lion blended in with the earth. This was their land - and we were the visitors. We soon found the pride's tracks at the V-bend in the river and spotted them lying in the shade of the Knob-Thorn Tree. Here they would rest for tonight's hunt. We spotted one particularly large male with the most beautiful, long blonde mane such as we had never seen before. With him were three adult females and five sub-adults. We quickly set onto our normal routine. We shot a Kudu, cut open the stomach and dragged it behind the vehicle. The scent would attract the lions. By sunset we had strapped the carcass filled with sleeping pills to a tree If the lions ate from the carcass they would become sleepy, thereby enabling us to dart them with less threat of attack. We were unsure if one Kudu would be enough especially considering the size of the male in the pride. Our camp was just1 kilometer from the Kudu carcass. After settling in, we talked about life and its lot. With over twenty tranquilizers ready to employ, we felt well prepared for what was ahead of us. We had one elephant caliber rifle, and my nine millimeter pistol; something I had grown accustomed to in the army. The caliber was relatively small, but its purpose was to scare away game. By 22:00 hours we had finished our meal for the night and we were ready to go to work. It was now time to begin playing recordings of lions mating and feasting to entice the lions into the area where the carcass hung. Just as we were about to play the tapes we realized that the pride was already indulging on our bait. We were quick to assemble, like a well-rehearsed rhythm. We all had done this so many times before. The Warden was driving the vehicle and the biologist switched on the red-filtered spotlight so as not to disturb the animals. I was the gunner, and I was carrying hope with me - the hope of survival. Despite our prior experiences, in cases like these you are never sure what you're getting into. It's nature; you simply cannot predict what may transpire. There is always the threat that the lion could jump onto the open back of the vehicle. We all accepted this threat as keepers of the land. It was another integral part of our mission which called us to this Ministry and ultimately we felt privileged to take these necessary risks in order to preserve this piece of heaven on earth. Not only did we bring hope to the lion, we also carried Namibia's pride on our shoulders. This was not work to us. We were giving something back to Mother Earth - to Africa. We were given the honour of helping her by blowing a bit of air into her lungs, even if only for these few of her children. As our vehicle approached the Kudu, the Warden switched off the main lights. All we could see was the red-filtered spotlight. We caught sight of one of the big females. The dart from my tranquilizer gun was quick and silent. It hit its mark. This sequence continued as the rest of the lions were successfully darted. It seemed that everything would go as planned. After all the lions were tranquilized and sleeping, we started the procedure of measuring the length and width of their teeth, and taking blood samples. These vital statistics were now marked in ink forever. As my rank dictated I had the privilege and honour to mark this blonde male with a radio collar. My hand brushed over his neck and I could feel his heart responding strong and hard. All I could think of is that he had no idea what was going on. Human ingenuity had tricked and fooled him into a deep sleep. Yet I could sense his immense power; this King of the Bush, this Ruler of Africa - her first born. What a glorious animal this was, sleeping in my arms. He was truly a perfect specimen, and we all smiled with the deepest sense of satisfaction, knowing that few would ever have this close of an encounter with such a beautiful animal in its native habitat. The radio collars would be used when tracking the lions to study their movements and every aspect of their way of life. We would learn from their wisdom of the land in their struggle for survival - their will to live. And in this world where you want to live forever, boundaries do not exist. The lions held so many secrets within them. And it made me feel weak as a human to interfere with these natural given rights bestowed upon them. We returned to our camp, allowing the hunters to sleep it off. Our wish was for this operation to be as peaceful as possible for them and not to bother them with our presence. But we knew this was impossible. My hope was only that the lions had had pleasant dreams of hunting antelope on the flood plains of Africa, guaranteeing their existence on this crooked earth of ours. I prayed that their dreams would remain pure and simple; survival and fitting into this very logical puzzle called Africa. Such a big piece the lion represents, justifiably admired by so many. Back at camp we were pleased with our success and our hearts sang from the work that we had done. We too quickly joined the dream world. This place where the stars are part of us, where the moon's soft light follows our hearts. As experienced Conservationists, we assumed our normal sleeping positions with our heads towards the vehicle. If danger should happen to wake us from our sleep, it would take us from our feet first as predators are threatened by the vehicle due to its size. Our feet and legs would warn us if the "black-cloaked man" was walking close by. As usual, I slept on my stomach with my pistol beneath my pillow. I suddenly woke from my deep sleep. My dreams were no more. As my mind adjusted to this new world, I realized that I was struggling to breathe. It felt to me as if all air had been pushed out of my lungs. A sudden pain shot through my body, ripping and tearing as it drove through my veins. The pain came from my neck and head, burning deeply. I was unsure of what was happening. "What could this be?" I thought to myself.  Knowing that I was in grave danger I gripped my pistol. It was as comforting as old friends shaking hands. By now I was as awake as any human could be. As a drop of blood slowly rolled down my face, I realized that Africa was yelling at me - for maybe I had done her some injustice. And then another drop of blood. The pain was burning, eating at my soul. I slowly turned my head. I looked up only to see this radio collar which I had assembled into place no more than an hour ago. My mind was quickly overwhelmed at the awesome strength standing above me, and lost in the indescribable furry I recognized in his eyes. His power drenched my soul and every little lost corner of my body with his majesty and with fear. The blood on my face was drying, but my mind was still racing at this tremendous pace - "What did I do to get into this situation?" My heart was beating at such a rapid pace that the vibration seemed to rock the earth beneath me.

Knowing that I was in grave danger I gripped my pistol. It was as comforting as old friends shaking hands. By now I was as awake as any human could be. As a drop of blood slowly rolled down my face, I realized that Africa was yelling at me - for maybe I had done her some injustice. And then another drop of blood. The pain was burning, eating at my soul. I slowly turned my head. I looked up only to see this radio collar which I had assembled into place no more than an hour ago. My mind was quickly overwhelmed at the awesome strength standing above me, and lost in the indescribable furry I recognized in his eyes. His power drenched my soul and every little lost corner of my body with his majesty and with fear. The blood on my face was drying, but my mind was still racing at this tremendous pace - "What did I do to get into this situation?" My heart was beating at such a rapid pace that the vibration seemed to rock the earth beneath me.

This sudden threat of death drove into my brain like a sharp nail. I wanted to yell, I wanted to scream, but I could not. Maybe it was God that kept me silent in this moment of peril. Death seemed imminent and my options were limited. There was only one way I could escape these jaws of death. I knew well that the lion was starting to feast. I had seen this so many times before. When the lion kills, he licks the skin off it's prey before he eats. Their tongues are covered in little hooks so as to remove all the hair and dirt from their prey's skin before feasting. This was not a good sign, at least not for me. The only option I had was to draw my pistol from underneath my pillow and fire a couple of warning shots in the air. The weapon's caliber was so small I could not risk wounding this lion in an attempt to kill him. A wounded lion carries with him all of Africa's furry and anger. And to stop such a lion is basically impossible. He wants to live and refuses to part from this world that he knows so well and loves so much. I had to fire the warning shots and pray that the exploding cartridges would scare him off. It was clear to me that this male; this beautiful young male was about to feast - from me. Again the lion licked me. I felt the warm ravine of blood tumbling down my face. My time was running out and I knew I had to act quickly. As my right hand grabbed my weapon, my left hand harnessing the pillow as a shield, I swiftly turned around to face the jaws of the hungry beast. Knowing that he would impale his teeth into my forearm, I shot off two warning shots as his jaws bit through the pillow over my arm. After the two shots were fired, the lion ran into the darkness. The campfire was still burning. There were still seven meters of light - or life . . . I got to my feet as quick as the southern winds bring the cold. My mind could not recognize how my body trembled and shook - as instinct once again took its place in the line of order for this moment of survival. The two other men opened their eyes only to see my world crumbling before them as the lion charged from amidst the darkness. I could not believe this. This was not supposed to happen. Again my weapon sounded in its cry for my life. I fired in front of the lion twice more, just at his feet - in an attempt to frighten him away. The lion abruptly stopped. When the lion stopped, we stared at each other for a while. It came down to this split decision; going for the kill, or saving this beautiful beast. Every time, despite my heart or how much my chance of life or death increased, for whatever reason I decided that I would try to scare him off. I fired two more shots; shots five and six at the lion's feet. Even if the lion charged, I had nine more rounds left in my magazine. I would still have the option to go for the kill if I was forced to. The lion stood his ground and turned towards me with his head held high. He was clearly in charge of this moment, and my fate. He took one step towards the darkness. For a brief moment the tension in my shoulders began to fade. Again the lion stopped and slowly turned around to face me one more time. My guard was up and I could feel the darkness caving in all around me. He was preparing for another charge. This animal that did not fear the sound of thunder nor the strange smell of man, he feared nothing. I lifted my weapon and fired another shot at his feet. I pulled the trigger again to fire another shot. But the shot did not go off. A quick glimpse at my pistol showed the slide-action pulled back indicating that there were no more cartridges in the magazine. I dropped the weapon to the ground and for a moment I was captured by the beauty of the full charge. Every stride he took; his blonde mane dancing and waving in the night air with the firelight as a backdrop. I could see his skin twitch as his muscles drove him closer to me. He did not blink his eyes and the power that was kept within them made me realize that death was inevitable. There was nothing I could do. The darkness smothered me and it felt as if the moon had fallen on top of me. I can't say exactly what happened next, but I caught myself flying on the wings of the flamingos over the vast flood-plains of the Caprivi. Stars took me by the hand and lead me to them, far beyond the Blue Mountains. They showed me how their reflections on the crystal clear lakes drove light into even the darkest corners. I was not afraid anymore. I felt good. I felt safe. The wind dried my tears. It sang a lullaby - a song that I only had dreamt of before. The moon stroked my cheeks with her gentle light. She pulled my eyes from the charging lion onto her; so beautiful and pure. Africa was talking to me and for the first time I could really hear her. I could understand what she was telling me. She was thanking me for the work I had done for her; protecting her holy grounds and treading on her soils rich and pure. Her words took the fear away and made me appreciate the privilege of life I have had so far. And as a gift I think, with the moon's light and the stars shining, a picture was painted on the dark skies of my lovely wife, her beautiful smile and warm eyes, her angel-like soul and lovely hands. They all reached out for me and it seemed that I could touch her, as if she was standing right in front of me, holding me. As if she was guiding me on this journey that fate had planned for me. She was beautiful. And I think if I could have seen Mother Earth's face that night, her image would have been that of my wife. With the grass's calming rustle, and the sweet smell of water from the floodplains, I was drawn back to reality. The lion was just four meters from me, charging. His eyes were glued to mine, and there was no escape. I was psychologically imprisoned by his might and his desire to kill. Again I could feel my wife's hand in mine and the moon as if it was shining from my heart. I was one of Africa's children and the time had come for me to go home. To join the million head-strong Blue Wildebeests migrating over the Serengeti Plains. I was but a grain of sand forming part of the Sahara masterpiece. I was the twinkle in the elephant's eye and the dolphin performing his ballet on the great oceans. I was the Fish-Eagle's cry and the Buffalo's unmatched power. She could take me now. I was ready to join her. I raised my hands up high and took my last gulp of air. Where I was going I would only breathe perfumed breezes. My heart thundered and exploded at the thought of this magical journey at hand and I feared no more. My eyes could no longer see the lion because they were swimming in a lake filled with rainbows. My skin could feel the cold no more and my hands no longer trembled. I sank to one knee and prayed to make this death a quick one. I wanted to join this world, where Wanda would find me one day too. A piece of rock flew up and hit me. That's how close the lion was by then. The beauty of it all was that I did not see the lion as a killer any more. I saw him as Africa's messenger. The carrier of good will. As our eyes met yet again, I did not see death anymore. I only saw heaven. This place of dreams where the rivers carry eternal life and where the trees never lose their leaves. I was not breathing anymore. I wanted to savour that moment forever. He turned away. He stopped only about a meter from me and slowly walked into the darkness. This glorious journey would have to wait for another day. My heart started to beat again. Tears came to me as I realized what had just transpired. I was given a second chance. God had given me a second chance. Praise be to the ways Africa is teaching us. Her methods are often hard, and may even seem cruel, but they are carried by the wind in perfect light and sound. I fell to the ground and started laughing. All that I could think of was my wife, and I longed for her touch and her warm embrace. When we were finally reunited, I told her how much I loved her. And there in her eyes were the lakes of rainbows I had seen as the lion came towards me. From that day forth I was carrying the moon in my heart. Africa is my home, and home to so many magnificent creatures. The need to protect is in my blood. It has been since I was born. I was blessed that day in so many ways, and promised the chance to continue to be keeper of Africa's sacred treasures. - The gift of my life in this heaven called Africa continues - An article written by Dries Alberts based on a true incident, which happened to Anton Esterhuizen |

|

||

|

Home *

About us *

About Namibia *

Hunting Areas *

Accommodation *

Information *

Prices * Articles * References * Fishing Safaris * Gallery * E-Mail * Copyright @ 2009 Estreux Safaris cc |

||||